The frequency of article releases has noticeably increased with the use of AI, and I intend to differentiate this in the tags within the text as well. The author’s column will also note the names of large models. However, the issue persists: articles generated by AI have significantly reduced my level of involvement, with many articles being forgotten after a month or so. This occurs similarly when writing code – instead of analyzing problems based on existing knowledge, I instinctively turn to AI for analysis and troubleshooting, leading to a clear increase in “laziness.”

Generative AI may boost work efficiency, but its “gift” comes at a huge cost. A research study at Peking University analyzed 410,000 papers and longitudinal experiments, finding that AI accelerates knowledge production but leads to severe homogenization; a Harvard study showed that AI causes “credential bias,” with junior positions decreasing by 7.7%, exacerbating the Matthew effect. On a personal level, the creativity boost brought about by AI is a fleeting “illusion” – it disappears when deactivated, but ideological homogenization persists, forming “creative scars.”

Current Situation

Generative AI is not only reshaping industries across the board but fundamentally altering how humans write, think, and reason. Following the release of ChatGPT3.5, an optimistic expectation spread widely: AI would bring about “work leveling.”

In 2023, two MIT economics PhDs published empirical research on this claim in the Science journal, providing evidence to support it: that generative AI significantly boosts the performance of low-performing employees, potentially bridging the gap with high-performing ones and reducing inequality.

The Science journal editors summarized this as, “Weaker participants benefited most from ChatGPT, a finding with important implications for policies aimed at reducing productivity inequalities through AI.”

However, two years later, reality seems to have not fully followed this ideal path.

In 2025, two Harvard economics PhDs, analyzing recruitment and employment data covering over 6.2 million employees and more than 1.5 billion instances between 2015 and 2025, revealed a stark truth: Generative AI is reshaping the labor market in a “credential-biased” way.

The data showed that between 2015 and 2022, the employment growth curves for junior and senior positions were roughly consistent, but starting in 2023, they began to diverge: Senior positions continued to rise, while junior positions started to decline.

For companies deeply embracing AI, the number of their junior-level positions decreased by approximately 7.7% over six quarters, while senior positions remained largely unaffected and even saw slight growth. This phenomenon was primarily due to a reduction in hiring rather than mass layoffs.

AI has not brought about equitable leveling but has instead exacerbated the Matthew effect – “the rich get richer.” Cheng Travel CEO Liang Jianzhang commented on the paper: “AI will replace basic intellectual labor, exacerbating the difficulties faced by young people in education, marriage and early career stages.”

The structural changes in the labor market are just the tip of the iceberg. A deeper question then arises: as AI is integrated into our workflows, what impact is it having on human creativity itself? Is the efficiency boost brought about by AI truly internalized individual capabilities? Is it shaping – or even “homogenizing” – our thoughts in ways we haven’t yet perceived? Once individuals become overly reliant on AI, is their independent, original thinking ability enhanced, or is it subtly being weakened?

Recently, Professor Li Guiquan’s research group at Peking University published a paper in the social science top journal Technology in Society, addressing these key issues head-on.

The core of the research comprised two parts. The first was a large-scale natural experiment that analyzed over 41,000 academic papers across all 21 disciplines before and after the release of ChatGPT3.5, dissecting AI’s true impact on global knowledge production. The second was a longitudinal behavioral experiment conducted over several months, exploring AI’s long-term causal effects on individual cognitive abilities in a laboratory setting.

Combining breakpoint regression design and machine learning techniques, the research team revealed generative AI’s long-term and genuine impacts on both individual creativity and group homogeneity.

This journal is JCR 1-star, with an impact factor of 12.5, ranking 271 out of 271 journals in the socialscience, Interdisciplinary category.

410,000 Papers’ “Collective Unconscious”

The most terrifying thing isn’t the noise, but the chorus of voices.

410,000 Papers’ “Collective Unconscious”

The study was a large-scale natural experiment.

The research team extracted academic outputs spanning all 21 disciplines – physics, life sciences and biomedical sciences, applied sciences, social sciences, arts and humanities – from the authoritative Web of Science Core Collection database. Through random sampling of over 17,000 scholars, the team ultimately collected all 419,344 papers published before and after the release of ChatGPT-3.5, constructing a massive dataset to analyze the true impact of AI on global knowledge production.

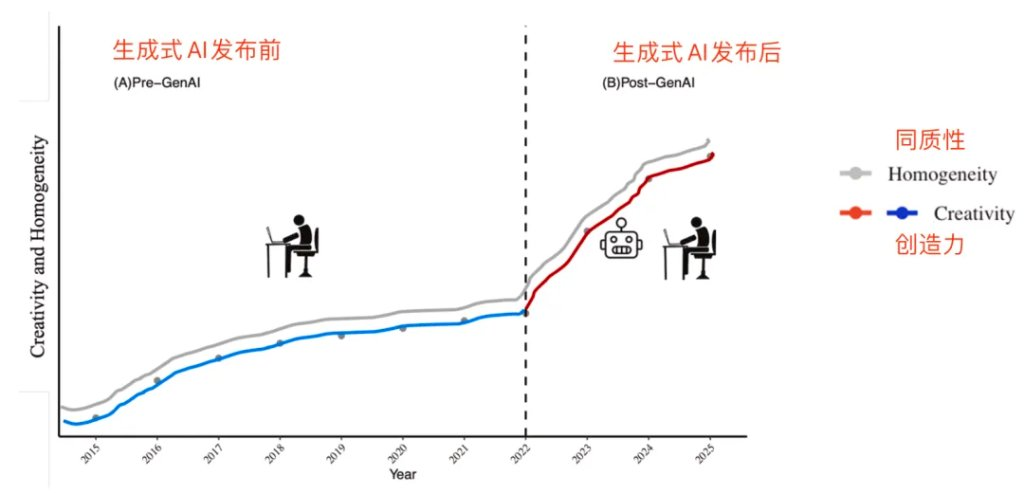

Illustration of homogeneity and creativity in academic papers before and after the release of Generative AI.

Illustration of homogeneity and creativity in academic papers before and after the release of Generative AI.

As shown in the figure above, prior to 2022, global academic output (red/blue lines) exhibited steady growth alongside homogeneity (gray line). However, following the release of ChatGPT3.5, both curves experienced a sharp increase in slope.

In other words, after GPT3.5’s release, academia not only accelerated knowledge production (creativity) at an unprecedented rate but also intensified the homogenization of its content at an even faster pace, clearly demonstrating the “double-edged sword” effect of generative AI on knowledge production.

To demonstrate that the observed changes were caused by AI and not due to chance, the research team employed a causal inference method called “Regression Discontinuity Design” (RDD).

How to Do

They viewed the release of ChatGPT-3.5 in December 2022 as a natural “time breakpoint.” Whether a paper was published before or after that date posed numerous uncontrollable factors for individual scholars (such as review cycles), effectively creating a randomized “experimental group” (with the opportunity to use AI) and a “control group” (unable to use AI).

Why it’s Reliable

This “pseudo-randomness” allows researchers to effectively isolate other long-term confounding factors and precisely identify the causal effects brought about by AI. To ensure the rigor of this method, the team also conducted a series of specialized statistical tests, confirming that scholars did not engage in strategic behaviors such as “delaying publication” or “early release” before or after the “breakpoint,” thereby guaranteeing the reliability of the research results.

How to Quantify “Creativity” and “Homogeneity” Metrics?

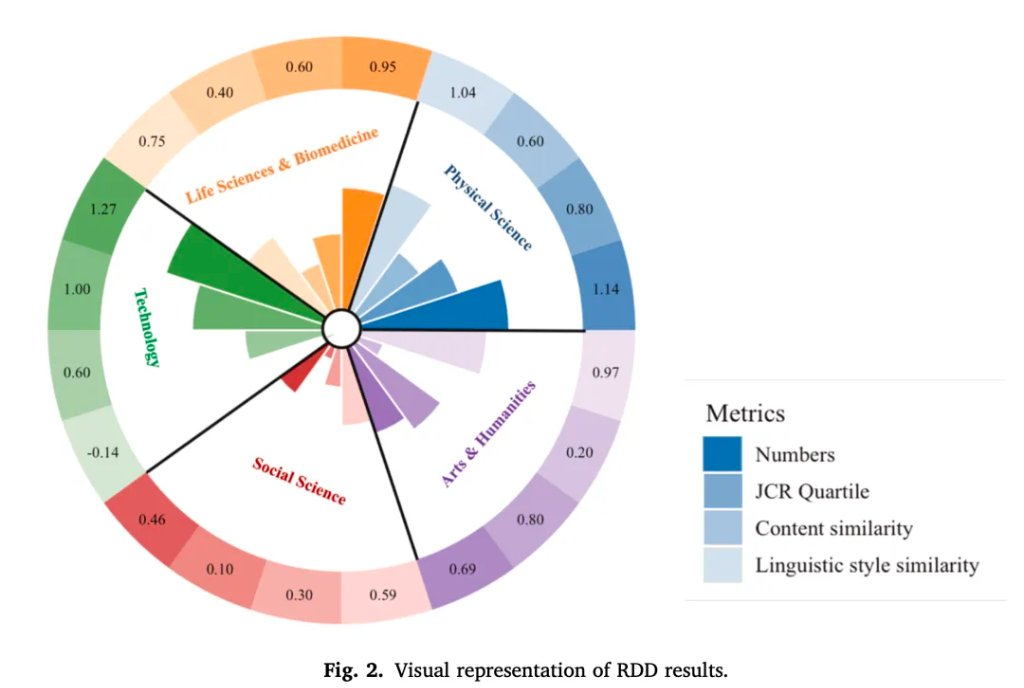

Following the confirmation of causality, the research team conducted a quantitative analysis of these 40+ thousand papers across two dimensions: “creativity” and “homogeneity.”

Creativity: Evaluated based on the number of paper publications and the quality of those publications (JCR Quartiles).

- Number: The total number of papers published by an author.

- Quality: The JCR Quartile score of the journal in which the paper was published. This is a prestigious journal ranking system, with Q1 representing the top 25% of journals in a field and Q4 representing the bottom 25%.

Homogeneity: Evaluated through content similarity and language style similarity.

- Content Similarity: Utilizing an SBERT deep learning model to convert paper abstracts into numerical “vectors,” then calculating the “cosine similarity” between these vectors to determine the degree of similarity in their core meaning.

- Language Style Similarity: Employing a character-level matching algorithm to scan and calculate repeated phrases and sentence structures between paper abstracts, thereby measuring the similarity of writing styles.

A Double-Edged Sword: More Efficient, Yet More Monotonous

As shown, the analysis results clearly reveal a “double-edged sword” effect.

On one hand, the emergence of AI has become a powerful “accelerator” for academic output: the average annual publication volume per scholar increased by 0.9 papers, and the quality of published journals averaged an increase of 6%. This effect is particularly prominent in fields such as technology and physical sciences.

However, on the other hand, the gains in efficiency are coming at the cost of diversity in thought and expression. Data show that the average annual similarity of writing styles in papers increased surprisingly by 79%, while the thematic content of papers also showed a significant convergence, with the most serious phenomenon being homogenization in physics, arts, and humanities.

This large-scale natural experiment conducted by Peking University researchers provides us with real-world macro evidence: Generative AI is indeed a powerful “accelerator” for academic output, helping scholars to produce and publish faster in better journals. However, this increase in efficiency comes at the cost of diversity in thought and expression.

Global knowledge production seems to be becoming more efficient and more “monotonous” in this “great exchange.”

Meanwhile, research two also left a deeper question: what does this macro trend mean for individuals who are immersed in it? Does the creativity boost brought by AI represent genuine personal cognitive growth?

To answer this question, the research team conducted a longitudinal behavioral experiment tracking over several months in a controlled laboratory environment in research two to explore the long-term causal effects of AI on individual cognitive abilities.

Scars of Creativity Left by AI

Once ideas submit to habit, they lose the possibility of creation.

AI’s Creative Scars

In fact, there have already been numerous laboratories using small-sample empirical studies from different angles to confirm the trends revealed by macro data. For example, research at Cornell University found that AI writing assistants sacrifice cultural uniqueness and cause users’ expressions to tend towards “Western paradigms”; research at Santa Clara University also showed that individuals who used ChatGPT were more similar in their creativity semantically.

Notably, a research team from MIT directly observed the brains of individuals using electroencephalography (EEG) technology, finding that the brain activity level of the group of students who used ChatGPT was significantly lower than that of the group that relied solely on their own thinking or used search engines.

These studies point to one conclusion: AI is sacrificing cognitive input and diversity to enhance efficiency.

However, most research focuses on the immediate impact of using AI, with little exploration of whether the effects of AI “leaving the field” can be sustained and whether its long-term negative impacts will diminish.

This study by Peking University made a new attempt in this area.

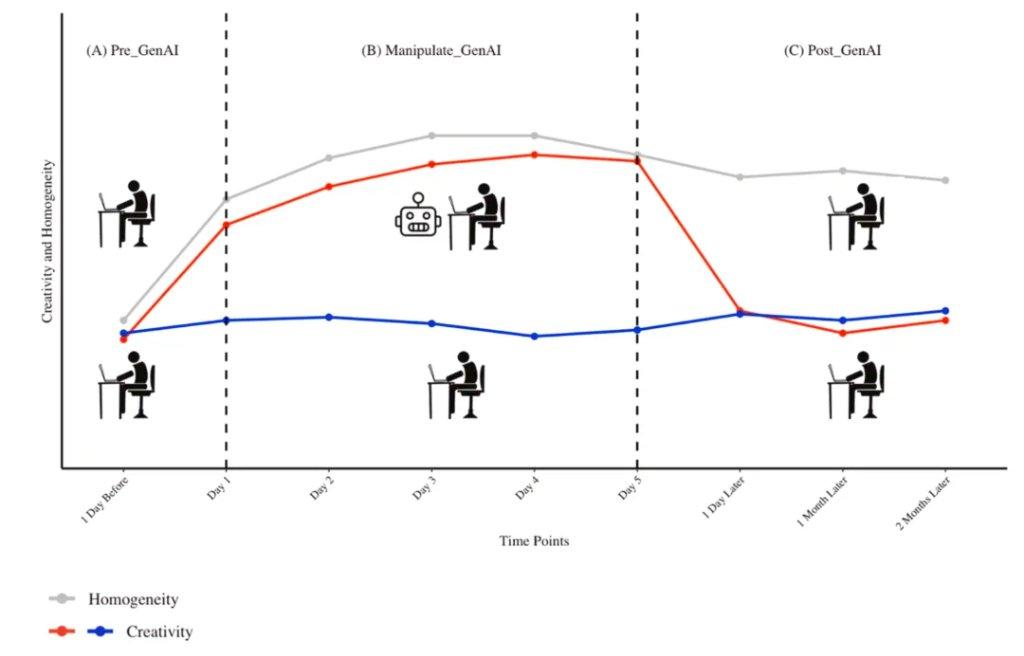

It not only observed the immediate effect of AI in a seven-day experiment, but also systematically tested the long-term consequences of AI dependence through two independent tracking tests after the end of the experiment – on day 30 and day 60. This allowed us to truly see whether what AI brought was a transferable “ability” or a fleeting, uninternalizable “illusion.”

Specifically, the Peking University research team randomly divided 61 college students into two groups: “AI experimental group” (able to use ChatGPT-4) and “pure brainpower control group.”

The experiment design consisted of three key stages: first, all participants completed a creativity baseline test on day one without using AI; then, from days two to six, the “AI experimental group” completed daily creativity tasks with AI assistance, while the “pure brainpower control group” completed the tasks without assistance; finally, and most importantly, on day seven, day 30, and day 60, all participants had to complete the final tracking test without any AI assistance.

To comprehensively evaluate “creativity,” the study used a composite task mode covering multiple dimensions. These tasks included:

To comprehensively evaluate “creativity,” the study used a composite task mode covering multiple dimensions. These tasks included:

- Divergent Thinking Test: The classic “Alternative Uses Task” (AUT), requiring participants to come up with as many novel uses as possible for everyday items (such as “a pen”).

- Creative Problem Solving: More realistic business scenario questions, such as asking participants to design innovative features for a “smart bicycle.”

- Convergent Thinking Test: The “Remote Association Test” (RAT) added during the tracking phase, requiring participants to find a word that can connect three unrelated words simultaneously.

- Insight Question: The classic “Candle Problem,” requiring participants to fix a candle on the wall with a box of nails, a candle, and a box of matches, without letting the wax drip onto the table. To ensure the scientificity of the assessment, the study used the “gold standard” in the field – expert consensus evaluation (CAT). Multiple expert judges independently scored thousands of creative outputs (including divergent thinking tasks and complex problem solutions) on multiple dimensions such as novelty, practicality, and flexibility in a “blind” condition where they were unaware of the grouping situation and research purpose. High data consistency (rating agreement ICCs > 0.90) ensured the scientific and fairness of the assessment results. The homogeneity measurement method used in Study II adopted the same technical methods as Study I to ensure consistency between the two studies’ evaluation standards. The experimental results clearly revealed a stark asymmetry:

- Creativity Enhancement is Transient and Unsustainable: During the AI usage phase (days 2-6), the “AI experimental group”’s creativity indicators were indeed far beyond that of the “pure brainpower group.” However, once the AI was removed, this advantage instantly disappeared. Starting from day seven until day 60, there was no significant difference in creativity performance between the two groups. More alarmingly, in the 60-day convergent thinking test, the participants in the experimental group’s performance was even significantly worse than that of the control group who had never used AI, what AI brought was not a transferable “ability,” but rather an uninternalizable “illusion.”

- The Homogenization of Thoughts is Long-lasting and Leaves “Creative Scars”: In contrast to the fleeting creativity enhancement, the homogenization of thought demonstrated surprising “stickiness.” Even after two months of not using AI, the output content from the “AI experiment group” – regardless of whether it was measured in terms of semantics or language style – still exhibited significantly higher similarity compared to the control group.

This longitudinal study provided direct causal evidence confirming the long-term impact of AI on individual creativity. The potential brought by AI may only be a “creative illusion” that cannot be internalized, while the resulting tendency towards homogenization of thought could become an enduring “creative scar,” persistently embedded in our cognitive and expressive habits.

If the world had no new creativity

It is the best of times, it is the worst of times.

If the World Lacked New Creativity

This research from Tsinghua University, concluding that we shouldn’t abandon AI entirely just because of our own frustration, instead aims to remind us that we must consciously understand and address the long-term impact of prolonged reliance on AI on individual thinking and cognitive habits.

The “homogenization” trend revealed in the study is rooted in profound principles of cognitive science: AI outputs easily trigger a powerful “anchoring effect” in users. When AI quickly generates an apparently “decent” answer or framework, our minds become anchored to this initial solution, making it difficult for subsequent thought and creativity to significantly deviate, ultimately leading to the convergence of ideas at the group level.

In July of this year, when Huang Renjun made a calm assessment during an interview with CNN: “If the world lacks new creativity, then the productivity gains brought about by AI will translate into unemployment.”

As generative AI is increasingly used, the internet’s information and human knowledge base are becoming more homogenized at an unprecedented speed. Tsinghua University’s research cold-heartedly confirms that this trend exists. If society can continuously generate new ideas, AI will create more diverse employment opportunities; if it only repeats old tasks, AI can complete them in seconds.

AI amplifies creativity but also accelerates the expulsion of “those with dry ideas.”

In the Age of AI, How to Maintain Sharp Thinking

AI alleviates our workload, but we need to establish a thinking system capable of deep thought, one that can interact with AI, articulate the problems we want AI to solve, and also engage in reasoning about those problems. Simultaneously, we must evaluate whether AI has answered correctly – we need dialectical thinking. —Huang Renfu

In the Age of AI, How to Maintain Sharp Thinking

As individuals navigating the age of AI, how should we position ourselves? How can we enjoy the convenience of AI while avoiding creative barrenness? Combining insights from research, here are some specific action recommendations:

-

Treat AI as a “Thinking Drill”: Consider it an tireless companion that provides unlimited perspectives. Use it for brainstorming, generating multiple possibilities, and challenging your ingrained assumptions. However, the final filtering, deepening, decision-making, and accountability for the results must always be yours.

-

Deliberately Practice “Cognitive Friction”: The most effective way to combat “anchoring bias” is to actively create “cognitive friction.” Don’t readily accept the AI’s first answer. Intentionally challenge it, find its logical flaws, and question aspects it hasn’t considered. This practice of critical thinking is key to maintaining our independent thinking abilities.

-

Establish “AI-Free Time”: Just as we need regular exercise to prevent muscle atrophy, we also need to regularly allow our brains to exercise without AI assistance. Regularly designate a weekly period of “AI-free time” for thinking, planning, and creating using the most basic tools – paper and pen or a blank document. This deliberate “cognitive detox” ensures that our core creative and reasoning abilities won’t deteriorate in comfort.